Racing Against time

To love something is beautiful but fleeting. What happens when you’re forced to let go?

By Aidan Eckhardt and Josh Berk

Photo By Liam Hamilton

Henry Tabor flies around the Wildcat spectator hairpin at the 2025 Olympus Rally, his co-driver, Jack Gillow-Wiles, calling the turns through a tight set of Washington woods.

To love something is beautiful but fleeting. What happens when you’re forced to let go?

Kristen Tabor, 51, checks the wheels one last time to make sure they are set properly. Her team’s 30 minutes are up, and she watches anxiously as her family pulls off in their Tabor-branded rally cars.

Tires spray dirt. People cheer and scream. The smell of gasoline hangs heavy over the racetrack.

She’s at a stage rally race. These rally races are held on gravel, dirt, snow, mud and all types of natural surface conditions. It’s an individual race. The drivers race against the clock. The co-driver must precisely read directions to the driver in a concise letter and number format, indicating road hazards ahead and estimated degrees of turns. All these elements and the ever-present danger of crashing into a tree or oversteering off a cliff results in an unforgiving but exciting form of racing.

Just two months ago, at their house in the Oregon City countryside, the Tabor family prepared for this race.

“I'm struggling with that because I don't feel like I have any relevance,” Kristen said. “I'm used to being the main character and now I'm just an NPC [Non-player character].”

“For whatever reason, we find enjoyment in going 100 miles per hour past trees,” Janice said. “ They just don't expect a grandma to be doing that.”

Rushing back into racing too early could be disastrous for Kristen’s recovery. Hanging up the keys isn’t easy for Janice and Kristen.

“I hate having to be an adult. I want an adult to make this choice for me,” Kristen said. “ I'm showing other women that they can go race cars too, just by being in the car and doing it.”

“ And they don't have to be 20-something to do it,” Janice added.

The periwinkle house that Kristen’s parents, Bruce and Janice Tabor, built 50 years ago, sits on the end of a long gravel driveway, along with a barn — it’s full of cars. A car graveyard lines the entry: some have patches of rust, some have split glass, and some are tucked under blue and grey tarps, mummified with moss.

The darling of the driveway is a blue 2003 Subaru WRX, “Smurfette.” Janice Tabor, 77, climbs inside the low race car as she’s done countless times before. Her short, white hair disappears from view as she swings her leg into the footwell. Sitting in the racing seat, she points out the roll cage and the kill switch: two essential safety components for stage rally cars.

Rally is tough on the cars and the drivers. The cars are constantly being rebuilt and re-specced. Rebuilding a human body isn’t as easy; these features are built in to keep drivers safe.

Smurfette bares marks of a mother and daughter’s racing adventures. Dozens of dents and dings freckle the car’s body. Stickers on the trunk lid read, “Girls just want to have fun,” “My mom and I talk shit about you,” followed by Janice and Kristen’s racing number: 231.

“She made it fly,” Bruce said, pointing to a decayed 1972 Dodge Dart, its once-orange paintwork now muted by time. “I didn’t make it fly,” Kristen said. The two recited their age-old argument about if the car once caught air while a teenage Kristen drove.

“I just kinda wanted to see how fast it could go,” Kristen said with a sly smile.

In the Tabor’s yard, retired rally cars sit, growing moss and building rust. Once pushed to their limits, these vehicles take their rest. Faded stickers and dented frames mark their history.

The kill switch is a safety feature that allows for instant engine and electrical shut-off in the event of a crash. This prevents the spread and ignition of fuel.

At the end of 2024, Kristen had back surgery. This ruined hopes for competing in the 2025 season. Janice won’t race without her daughter. They were adored in the community, and without the two Tabors, rally lost a beloved and all-too-rare female team.

The sport has a high bar for entry. Starting out costs at least $25,000 for a beginner car, $5,000 for safety precautions and potentially thousands more for lodging and travel. Permits for closed roads, safety crews and months of planning make the organizational side of putting on a rally difficult as well.

“ It takes a lot to put a rally on, but so little to get it taken away,” Kristen’s nephew Henry said. This could mean a permit being pulled or a driver suffering an injury, to name a few.

Kristen and her mother and co-driver, Janice, are accountants like the rest of their family, but their passion is motorsport.

“ One of the reasons I want to get back in the car so bad is because representation matters,” Kristen said. “The more women see women in the driver's seat, the more women will feel like ‘I can go race.’”

Historically, stage rally racing is a male-dominated sport. Women make up only 7 to 13 percent of participants overall, according to the More Than Equal report, Inside Track: Exploring the Gender Gap in Motorsport. One of the main barriers is a lack of visible role models. The passion to be the next racers to inspire women fuels Kristen and Janice Tabor’s desire to compete.

This has resulted in an abundance of medals and podium placements, as well as injuries significant enough to consider ending their racing careers. Giving up this long-time passion had nothing to do with a loss of interest, but understanding their limits.

The roll cage protects passengers during rollovers, forming a barrier between you and the frame. Rally cars like the Tabor’s blue “Smurfette” reflect their drivers – a glimpse into the personalities of the racers.

Kristen is hesitant to declare rally racing as the definitive source of her back injury, but she says she can’t rule it out as a factor.

A major accident flipping of the vehicle is known as “rolling” the car. Rolling is semi-common in the world of rally racing. Kristen and Janice have rolled twice. “I get to roll once every 25 years,” Kristen said.

“Kristen and Janice went 15 feet in the air and pirouetted down the hill into the stump of a tree,” Bruce said.

The fear of concussions, broken ribs and death, lives in the back of drivers’ minds. This high-speed, high-stakes sport leaves some racers to ask if risking their health is really worth it. Some racers answer that question earlier than others.

Ed Millman sits in his garage in front of his red 1989 BMW 325iX and a stripped-down 1951 Cooper 1100 V Twin awaiting its new coat of baby blue. Millman was a stage rally racer himself, usually a co-driver, until he gave it up for safer avenues.

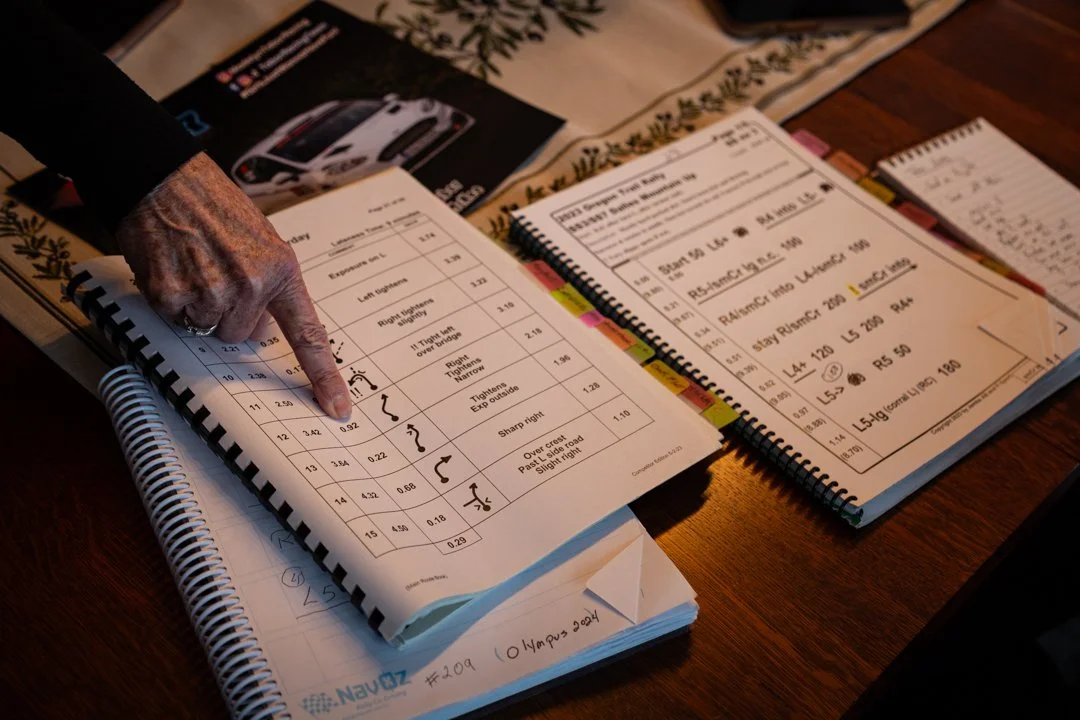

Pace notes are a unique set of symbols and numbers, the roadmap for which co-drivers direct drivers through each distance, corner and obstacle.

“ There was a couple of pretty good-sized accidents that I was in, and that was right about the time that I got married and started having kids,” Millman said.

Lately, time speed distance rally racing has been Millman’s primary outlet for motorsports. TSD rally is a distance event done on open roads going under the speed limit. The art of being perfectly on time, down to the tenth of a second.

Mother-daughter rally duo Janice, 77, and Kristen Tabor, 51, have spent 25 years tearing up the track. They share matching dragonfly tattoos, a symbol of their driving, and “237,” their racing number.

“ Probably the biggest risk you have in a TSD car is that you're going along and you have to make some kind of evasive maneuver,” Millman said. “In a TSD car, you've got clipboards and pens and pencils flying around and things like that. You probably get hurt by one of those as much as anything.”

With a new focus, Millman can safely continue to be a part of car and racing culture. But staying out of trouble is easier said than done. Where Millman decided to take a backseat, Kristen chose a different way to stay involved in the family hobby. She’s been volunteering her expertise in rally events as a crew chief.

Kristen Tabor, crew chief of the Tabor Racing Team, oversees operations as drivers check in at Sanderson Airfield for a 30-minute service window at the 2025 Olympus Rally. Teams must clock in and out at the entry and exit, keeping to a 15 miles per hour speed limit.

The dynamic between driver and co-driver is difficult to master. It's built on trust, timing and an understanding of each other’s rhythm. The two have to mesh just right, and it can take a lifetime to find a good pairing. Unless you’re born to the perfect co-driver like Janice and Kristen.

Co-driver Kathryn Hansen flashes the three fingers to confirm the three-minute mark on their service time as driver Mark Tabor gears up to hit the stage at the 2025 Olympus Rally.

Despite — or possibly driven by — her urge to compete again, Kristen has fit right in servicing the vehicles. She moves with surgical precision at the airstrip where the cars come in for repairs and tuning.

Janice is missing this race. She’s visiting her granddaughter in Washington, D.C. She texts Kristen often, eagerly waiting for updates.

“ It seems like every single time [the racing team] starts coming to service, I get a text. ‘How's it going? What's going on?’” Kristen said, laughing.

Chaos ensues as the Tabor pit crew makes last-minute preparations during their service time at the 2025 Olympus Rally on April 13

Mark Tabor flies around the Deckerville spectator area hairpin, kicking up a cloud of dust during a gravel stage at the 2025 Olympus Rally on April 12.

Henry Tabor and his dad, Mark, placed second and third in their respective classes. Madelyn doubled her speed factor — a complex measuring system of how fast drivers are going — at this race, earning her and her co-driver a large check and recognition at the podium ceremony. But Kristen and Janice made it clear: they want to join the rest of their family on the podium again.

“The Tabor’s are a staple in Rally. If there’s not a Tabor in the rally, can you really call it a rally?” Ed Flaisig, the man announcing every car pass with a megaphone, said.

“Unless there are at least two,” Kristen Tabor said.

The mother-daughter duo said they haven’t felt closure within racing. They can already picture what closure will look like: a podium placement, a champagne spray and a party. Kristen hopes that day will come soon. Until then, she’s found joy in her new role on the family team.

Champagne flies as Henry Tabor (right) and Jack Gillow-Wiles (left) celebrate 2nd in Limited Two Wheel Drive at the 2025 Olympus Rally, with Mark Tabor (right) and Kathryn Hansen (left) in 3rd.

Janice has only co-driven for Kristen, her husband, Bruce and her granddaughter, Madelyn Tabor. The irreplaceable bond she shares with Kristen makes it difficult to adapt to drivers.

Sidelined during Kristen’s recovery, Janice is experiencing something of an identity crisis herself.

“ I can't figure out where my place on the team is right now. Kristen has taken over as crew chief and I will assist her, but I don't really have an identity on the team yet,” Janice said.

She has slowly been taking on a supporting role on the crew.

“ It's definitely not the adrenaline rush to being in the car, I'm gonna tell you that. I still miss that,” Janice said.

“Rallying is a disease for which there is no known cure,” Bruce said. Nowhere is that more evident than at the Olympus Rally in Shelton, Washington. Fans bushwack and wait hours in advance to see their favorite racers drift by for no more than a few seconds at a time.

Afterward, drivers honk their horns and showboat at large turns to thrill the spectators.